Not a virus: What it means and why antivirus software flags it

Seeing “not a virus” in an antivirus alert can be confusing. The file has been flagged, but it hasn’t been blocked or clearly labeled as malware. What this means, and how to respond, isn’t always obvious from the alert alone. It can be hard to know how seriously to take the warning.

In this guide, we explain what a “not a virus” detection means, why antivirus software uses this label, and how it differs from malware. We also cover potential privacy and security risks and what to do when you see this alert.

What does "not a virus" mean?

“Not a virus” is a label antivirus software uses when a file doesn’t match known malware but still triggers a detection. The file isn’t blocked automatically or treated as a confirmed threat. Instead, the alert is meant to flag something unusual and leave the decision to the user.

This type of alert usually happens when software behaves in a way that antivirus tools associate with higher risk, even though there’s no clear sign of malicious intent. In other words, the file wasn’t flagged because it’s known to be harmful, but because the antivirus can’t confidently classify it as safe either.

Why “not a virus” isn’t the same as malware

Malware, or malicious software, is software created to cause harm, such as stealing data, encrypting files for ransom, or giving attackers unauthorized access to your systems or your data. When antivirus software detects malware, the file is usually blocked or quarantined automatically.

Antivirus suites mainly find malicious software in two ways:

- Signature detection: Checks file patterns against a database of known threats.

- Heuristic and behavior-based detection: Observes file behavior for typical signs of malware as it runs, even if the file doesn’t match a known signature. Antivirus software using heuristic analysis can check files without running them, and it combines multiple red flags to give a “best guess” detection.

Files are usually labeled “not a virus” because they don’t match a known malware signature or behavior, but they’re capable of actions that raise security concerns. For instance, a remote desktop tool allows someone to control a computer from another location. IT teams use this for legitimate technical support, but an attacker could use something similar to spy on a device.

Antivirus software can identify what a program is capable of doing, but it can’t determine who installed it or how it’s being used. Because intent and context aren’t visible during scanning, certain files aren’t classified as malware and may not be blocked automatically.

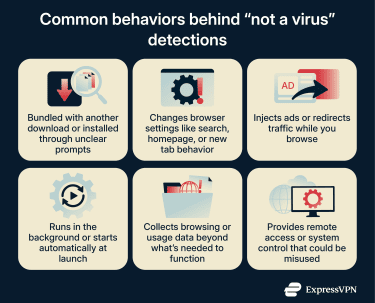

There’s also a difference in how these programs typically arrive. Malware usually installs without meaningful user involvement and tries to stay hidden. Software flagged as “not a virus” is often installed intentionally or bundled with a legitimate download.

Related: What’s a possible sign of malware?

Legitimate tools that may trigger “not a virus” warnings

These are some of the programs that can trigger a “not a virus” alert, even when they’re safe and downloaded intentionally.

- System utilities: Tools that need low-level access can trigger alerts because they read or inspect sensitive parts of the system. For example, a password recovery tool may read saved credentials or browser storage and can trigger an alert.

- Download managers and torrent clients: These programs pull files from many external sources, keep long-running background transfers, and may add browser extensions or change browser settings to manage downloads. Constant inbound files plus background persistence is a common pattern in unwanted software.

- Game cheats and key generators: These tools often patch program files, change memory values while an app is running, or bypass license checks. Modifying other programs and defeating protections is the type of behavior antivirus tools frequently classify as suspicious. Note that these files can also be vectors for actual malware, disguised as cheats.

Common types of "not a virus" detections

Adware

Adware is software that generates revenue by displaying ads or redirecting your traffic. For example, in-browser adware might open a pop-up or new window that takes you to an advertiser’s website.

Some ad-supported software discloses its nature during installation. In other cases, disclosure is buried in terms of service.

Antivirus software usually flags adware when it injects ads into web pages, opens pop-ups outside the browser, changes search or homepage settings, or tracks browsing activity across sites. The more invasive or persistent the behavior, the more likely it is to trigger detection.

Riskware and potentially unwanted applications (PUA)

Riskware refers to legitimate software with capabilities that could cause harm if misused. Remote access tools, password recovery utilities, and network administration programs fall into this category.

PUAs are flagged for a different reason. The concern isn't about powerful capabilities but about how the software arrived. Programs bundled with other software, installed through deceptive prompts, or added as pre-selected optional components often fall into this category.

Antiviruses don't always separate these cleanly. Some group them together; others use different labels entirely. What riskware and PUAs share is that the software isn’t always malware, but it’s generally flagged to draw your attention.

Programs commonly flagged as riskware or PUA

- Cryptocurrency miners: Programs that use system resources to mine cryptocurrency, particularly when they run in the background without clear disclosure. Legitimate software should never hide these tools without your consent.

- Monitoring tools: Software for parental control, employee monitoring, or auditing that records keystrokes, screen activity, or application usage.

- Browser extensions and toolbars: Add-ons that modify search or homepage settings, inject content into pages, or collect browsing data beyond what’s needed for basic functionality.

Is “not a virus” dangerous?

Potential security impact

The main security risk of a “not a virus” file is usually exposure rather than a direct attack.

In most cases, these programs aren’t the source of a security incident. They typically don’t introduce exploits or self-propagate the way malware does. Instead, they can worsen existing security issues.

That could be a weak password, an unpatched system, or someone gaining access they shouldn’t have. For example, remote access software can be hijacked on a poorly configured device. On a system with strong security measures in place, the added risk is often small.

Potential privacy impact

Privacy issues are often more common than direct security threats with “not a virus” files.

Programs in this category may collect usage data as part of how they operate. This can include the websites you visit, search terms entered through the software, or interactions with ads or features. They might also collect basic device details such as operating system, IP address, or language settings.

That information may be sent back to the software’s developer and, in some cases, shared with analytics or advertising partners.

Over time, repeated data collection can make it easier to link your activity across sessions or services. For example, browsing behavior captured by a browser extension or ad-supported program might be combined with other signals to build a profile. That profile can then be used to tailor ads, measure engagement, or group users into interest categories.

What to do if your antivirus detects “not a virus”

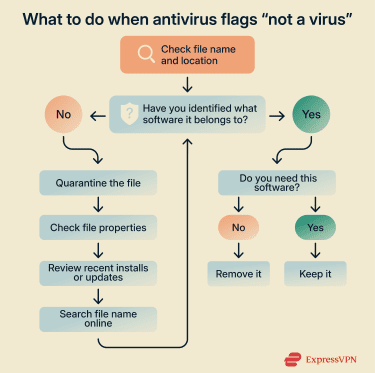

Step 1: Identify the file

Start with the file name and location shown in the alert. The file’s properties can also reveal who created it (under “Publisher”).

If you can’t connect the file to any software you remember installing, quarantine it using your antivirus tool. Quarantine stops the file from running but doesn’t delete it, giving you time to confirm what it is before deciding whether to remove it permanently.

Step 2: Review recent changes

Check what you installed or updated just before the alert appeared. If the timing lines up with a recent download, update, or installer, the detection is likely related to that change.

If nothing recent explains the alert, check whether the file is set to run at startup or appears as a browser extension. These are common places for unwanted components to persist.

Step 3: Compare detections (optional)

If you’re still unsure, you can run an online search for the exact file name to see if anyone else has identified it in the past. You can also look at how different antivirus engines label the file using a multi-engine scanning service. This can provide additional context, not a definitive answer.

Seeing how widely a file is flagged can help you understand whether the detection reflects a broader pattern or a single vendor’s criteria. Use this information to inform your decision rather than relying on it alone.

Note: Avoid uploading files that contain personal, sensitive, or confidential data.

Step 4: Decide whether to keep or remove it

Focus on whether you need the software and whether you’re comfortable with the behavior that triggered the alert. If you don’t use the program, didn’t intend to install it, or don’t want the flagged behavior, there’s little reason to keep it.

If you rely on the program, keeping it can be reasonable, but check if the flagged behavior is expected and can be limited or disabled. If it can’t, switching to an alternative may be safer.

Step 5: Remove the software and check for leftovers

If you’ve decided the software isn’t something you want, remove it using your operating system’s standard uninstall process. If you can’t find it in your system, use your antivirus tool’s removal option rather than deleting files manually.

After removal, check for leftover changes that may have been introduced by the software. Browser extensions, startup programs, and homepage or search engine settings can remain even after the main program is gone.

If you’re worried about an active infection, see our guide on signs your computer has a virus and how to remove it.

How to reduce unwanted "not a virus" alerts

A few habits can reduce how often these alerts appear:

- Download from official sources: Software from trusted developer websites or official app stores is less likely to include bundled extras that trigger detections.

- Use custom installation options: Select advanced or custom installation when available. This reveals optional components that would otherwise be added to your device automatically.

- Remove software you no longer use: Background services and scheduled tasks can remain active long after you stop opening a program.

FAQ: Common questions about “not a virus” alerts

What does “not a virus” mean in simple terms?

It’s a label antivirus software uses for files that aren’t malware but still trigger a detection. The file isn’t blocked automatically because it isn’t known to cause harm. The alert highlights software that may be unwanted or unfamiliar, so the user can review it.

Is “not a virus” actually malware?

No. Malware is designed to cause harm, such as stealing data or taking control of a device. Software labeled “not a virus” doesn’t meet that definition. It may still be intrusive or unnecessary, but it isn’t classified as malicious.

Why do antiviruses flag safe software as “not a virus”?

Antivirus tools evaluate how software behaves. Programs that change system settings, run in the background, or add system components can trigger a detection even when they’re legitimate.

Can legitimate programs trigger “not a virus” alerts?

Yes. Programs used for support, customization, or system access can trigger these alerts. This includes tools that install background services, browser add-ons, or helper components. The detection signals that the software does more than basic file execution.

What should I do if I receive a “not a virus” warning?

Identify what the file belongs to and whether you intended to install it. If it’s part of software you rely on and the behavior is acceptable, keeping it can be reasonable. If you don’t recognize it, don’t use it, or aren’t comfortable with what it does, removing it is usually the better option.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN