What is SQL injection? How it works and how to prevent it

Most websites store information like usernames, passwords, and payment details in databases. When you log in, search for a product, or submit a form, the site sends a request to its database to fetch or update matching records. SQL injection (SQLi) is an attack that adds extra instructions to those requests, changing what the database is asked to do.

The technique has been around for over two decades, yet it remains one of the most common ways attackers breach web applications.

What is SQL injection (SQLi)?

Structured Query Language (SQL) is the standard language websites use to communicate with databases. SQL injection (SQLi) is when an attacker adds extra SQL instructions to a database request, like an entry in a form on a website.

Normally, form input should be read as a value, like a username or password, not as instructions for the database to follow. SQLi works when a website takes what a user types into a form and places it directly into the request sent to the database.

If an attacker types carefully crafted input, those instructions become part of the request. The database has no way to tell the difference, so it follows the attacker’s instructions.

Why the SQL injection vulnerability exists

SQLi is possible because of the way some applications build database queries. Instead of keeping the query logic (the fixed instructions that tell the database what to do) and user input separate, the application assembles everything as a single block of text. By the time the database receives it, there’s no distinction between instructions written by the developer and values supplied by the user.

This is known as string concatenation. It was common in early web development because applications often built queries by manually assembling text strings, and databases didn’t enforce a clear separation between instructions and values.

Today, most programming languages provide ways to avoid SQLi. For example, a developer layer library can sit between the application and the database to separate instructions from user input. The library then sanitizes (checks and amends) the user input before concatenating the query and sending it on to the database.

However, SQLi vulnerabilities can still show up in legacy or custom-built systems. Older code, tight deadlines, and limited security awareness mean these safer approaches aren’t always used.

What SQL injection can achieve

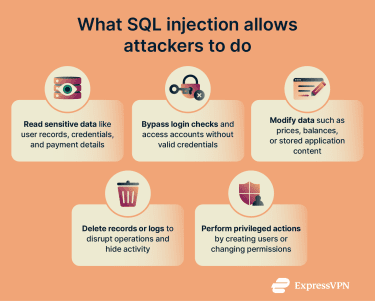

The damage an attacker can cause depends on the permissions granted to the database account the application uses. When SQLi is possible, attackers may be able to:

- Read sensitive data: Attackers may be able to pull information directly from the database. This can include user accounts, login details, payment records, or other data the application is allowed to read.

- Bypass login checks: The application may grant access even when the provided login details are incorrect.

- Change or delete data: If the application has permission to write to the database, attackers may be able to update values like prices or account balances. They may also delete records or remove logs that would normally show the interference.

- Perform privileged actions: If the application uses a highly privileged database account, attackers may be able to create new database users or change access permissions.

- Reach the server itself (rare): In some legacy or poorly configured systems, the database account may have unusually high privileges that allow it to interact with the underlying server. In those cases, SQLi has been used to read server files or run system commands. However, this depends on additional system misconfiguration and isn’t typical of modern deployments.

Related: What is password hashing?

Types of SQL injection attacks

SQLi attacks all exploit the same underlying weakness, but they don’t all play out the same way. Some use different methods to get results back from the database, while others involve injected input being stored and only causing problems later in the application.

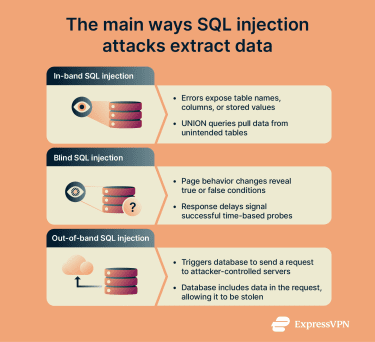

In-band SQL injection (classic SQLi)

In-band or classic SQLi is the most direct form. The attacker sends crafted input, and the database's response appears directly in the application.

This usually happens in one of two ways:

- Error-based SQLi: If an application displays database error messages, those errors can reveal details such as table names, column names, or stored values. Attackers can deliberately trigger errors to learn how the database is structured.

- UNION-based SQLi: SQL includes a feature called UNION that combines the results of two queries into a single response. If attackers can inject a second query using UNION, they can sometimes pull data from a different table. For example, a product search page could be manipulated to return user records alongside product listings.

Inferential SQL injection (blind SQLi)

Inferential or blind SQLi occurs when an application doesn’t display query results or error messages. Attackers can’t see data directly, so they infer it by observing how the application responds to different inputs.

Blind SQLi is slower than in-band methods, so attackers usually automate it using scripts that send large numbers of requests and record the results.

Out-of-band SQL injection

Out-of-band SQLi is another technique that can be used when attackers can’t get data through the application itself. Instead, they add input that causes the database to send a request to a server they control, with the desired data included in that request. When the request arrives, the attacker can read the data directly.

This method only works if the database is allowed to make external connections. Most real-world systems block these connections, which is why out-of-band attacks are less common.

Second-order SQL injection

In second-order SQLi, the injected input doesn’t cause a problem right away. Instead, it’s stored by the application and later reused in a different database query. When that stored value is inserted into a new query without proper handling, it can trigger SQLi.

This type of attack depends on unsafe reuse of stored data across different parts of an application and is also less common than other methods.

Notable SQL injection attacks

SQLi has been used in real intrusions that led to large-scale data theft. The cases below show what this vulnerability can lead to.

Heartland Payment Systems, 7-Eleven, and Hannaford Brothers (2006–2008)

U.S. prosecutors alleged that attackers used SQLi to break into multiple payment-processing and retail networks, then placed malware to capture payment card data. In Heartland’s case, the data theft involved more than 130 million credit and debit card numbers.

TalkTalk (2015)

The UK telecom TalkTalk was breached after attackers exploited a website vulnerability described by the UK regulator as including SQLi. The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) said the incident exposed customer data and later issued a £400,000 fine (approximately $547,000) for security failings.

Related: Biggest cyberattacks in history

How to detect SQL injection vulnerabilities

Finding SQLi flaws before attackers do usually requires more than one approach. Some methods look for problems in the code itself, while others observe how the application behaves when it's running. Each catches different kinds of mistakes, which is why organizations tend to use them together.

Automated testing

Automated tools are often the first step. They scan applications for common signs of SQLi.

Static Application Security Testing (SAST)

SAST examines source code directly. It looks for places where user input is combined with database queries in unsafe ways, such as joining text strings together. This helps catch problems early, before the application is deployed.

However, SAST can flag issues that aren’t actually exploitable, since it analyzes code without running it. It can also miss problems that only appear when the application is live and handling real input.

Dynamic Application Security Testing (DAST)

DAST tests the application from the outside, similar to the way an attacker would operate. It submits modified inputs through forms, URLs, and other entry points, then watches how the application responds.

Error messages, unexpected page changes, or unusual response times can all indicate a flaw. Because DAST tests the live application, it catches issues that aren't obvious from reading code alone.

Interactive Application Security Testing (IAST)

IAST combines both approaches by observing the application while it runs and tracking how input moves from the user to the database. This provides more context and helps reduce false alarms, but it requires deeper access to the application.

Two open-source tools are especially common for SQLi testing:

- SQLMap: Focused on SQLi testing and validation.

- OWASP ZAP: A broader scanner that includes injection testing

Automated testing is efficient and scalable, but it has limits. Complex application logic and unusual input handling can still hide vulnerabilities.

Manual testing and code review

Because automated tools don't catch everything, manual testing is important too. Testers start by identifying every place the application accepts input. This includes visible elements like search boxes and login forms. It also includes cookies that remember your session or values passed through the web address, known as URL parameters, that tell the page what to display.

Testers can then submit specific inputs designed to produce responses that indicate unsafe input handling. Common tests include:

- Single quotes: Often break SQL string syntax and trigger database errors when input isn't handled safely.

- Boolean conditions like

OR 1=1: Used to check whether changing query logic affects the application’s response, which suggests unsafe input handling. - Time-delay commands: Cause the database to pause before responding, indicating the input is being executed rather than treated as data.

Code review takes a different approach. Developers or security reviewers read through the application's code to see where user input is used in database queries. If they find places where input goes directly into a query without protection, those sections are marked for fixing.

How to prevent SQL injection attacks

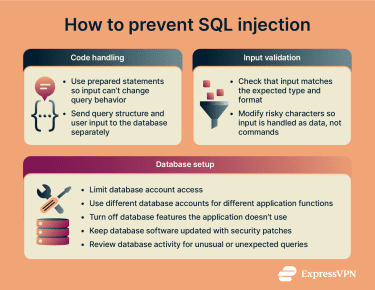

Preventing SQLi relies on one core rule: user input must never be able to change what a database query does. The database should receive clear instructions about what to run and treat everything supplied by a user strictly as data.

The measures below work best when they’re used together.

Using prepared statements (parameterized queries)

The most effective defense against SQLi is to use prepared statements, also known as parameterized queries.

With this approach, the application sends the database a query template first. That template defines the structure of the query, such as which table to read from and which conditions apply. User-supplied values are sent separately and placed into predefined positions, so they can’t change how the query behaves.

Because the database already knows which parts of the query are instructions and which parts are values, user input can’t alter the query’s logic.

A vulnerable query built by joining text together looks like this (whatever the user types becomes part of the query itself):

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = [user input]A parameterized version keeps instructions and data separate:

query = "SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = ?"

execute(query, userInput)The placeholder “?” marks where the value belongs. Even if an attacker submits 'OR '1'='1’, the input is handled strictly as data and can’t change the query’s logic.

Input validation and sanitization

Input validation checks whether user input matches what the application expects before it reaches the database.

If a field is meant to contain a numeric ID, anything that isn’t a number should be rejected. If a field expects a specific format, input that doesn’t match that format should be blocked early. This limits what input the application accepts and catches obvious problems before they reach the database.

Validation only checks the format. An attacker can still submit input that looks valid but contains characters with special meaning in SQL, such as single quotes. Validation won’t catch that.

Sanitization tries to address this gap by modifying risky characters so the database reads them as text rather than as SQL syntax. For example, if a user submits input that includes characters that can change how a query is interpreted, the application may modify those characters so they’re treated as text rather than affecting the query itself.

The issue is that different databases handle this differently, and mistakes are common. Sanitization can help, but it’s fragile. It works best as a supporting measure alongside prepared statements, not as a substitute.

Secure database configuration and access controls

Even when an injection flaw exists, the impact depends on what the database account is allowed to do. To reduce the scope of potential attacks:

- Limit account permissions: Applications should only connect to the database with the permissions they actually need. If a part of the application only displays product listings, its database account shouldn't be able to change user records or access administrative tables.

- Use separate accounts for different functions: Where practical, different parts of an application should use different database accounts. For example, the code that handles public searches shouldn't use the same account as the code that manages user data. If one part contains an injection flaw, the attacker is limited to that account's permissions.

- Disable unnecessary database features: Some databases support features that let queries read files from the server or interact with external systems. If the application doesn't rely on these features, they should be turned off to limit an attacker’s reach.

- Keep database software up to date: Patching doesn't fix unsafe query handling in application code, but it can close known vulnerabilities and reduce the impact if an attacker reaches the database.

- Watch for unusual database activity: Databases can record the queries they receive. Reviewing these records can help spot problems, like repeated errors or access to tables the application doesn’t normally use.

FAQ: Common questions about SQL injection

Can SQL injection be completely prevented?

In practice, yes. Using prepared statements for all database queries removes the primary SQL injection (SQLi) vector. Input validation and limited database permissions further reduce risk, but a single unsafe query can undo these protections.

What are the signs of an SQL injection attack?

Signs usually appear in application and database logs, not on the page. Common signs of SQL injection (SQLi) include database syntax errors triggered by user input. Logs may show queries accessing tables that the application doesn’t normally use. Repeated failed queries with unusual parameters are another warning sign. Response delays can also indicate time-based probing.

Is SQL injection still a threat today?

Yes. SQL injection (SQLi) still causes real-world breaches. It also appears in the Open Worldwide Application Security Project (OWASP) Top Ten, a widely used list of the most serious web application security risks. Legacy code, inconsistent secure coding practices, and poor maintenance keep the risk alive.

How often should SQL injection testing be performed?

After any meaningful change to code that interacts with the database. Teams usually test after deployments that modify queries or input handling. Applications that process sensitive data are tested on a regular schedule, and many teams also run automated checks during development to catch issues early.

Which tools help protect against SQL injection attacks?

Web application firewalls, security testing tools, and database monitoring tools can help. Firewalls can block known attack patterns, scanners can find weak spots in the code, and monitoring tools can spot suspicious database activity.

These tools lower the risk of an attack, but they can’t stop SQL injection (SQLi) on their own. The application still needs to build database queries safely.

What is the business impact of an SQL injection breach?

It can be severe. An SQL injection (SQLi) breach can expose customer data, disrupt services, and force emergency fixes. Businesses often face investigation and cleanup costs, possible fines or legal action, mandatory customer notifications, and long-term reputational damage that affects trust and revenue.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN