Who owns an IP address and how a VPN keeps yours private

Think your Internet Protocol (IP) address belongs to you? Not exactly.

Every time you go online, your home network and devices are identified by IP addresses that can reveal your approximate location, the provider of your connection, and ownership details, which are often stored in public databases. With basic tools, it’s surprisingly easy to look up who controls a block of IPs and infer things about the people using them.

In this guide, we’ll break down who actually owns an IP address, how those ownership records work, and how a virtual private network (VPN) can help you stay more private online.

What is an IP address?

An IP address is a string of numbers that identifies your connection on a network. When you go online, websites know where to send the data back. Without IP addresses, the internet wouldn’t know how to deliver anything to the right place.

At home, this actually happens at two levels. Your router assigns each device a private IP address so they can communicate within your local network (for example, when your laptop sends a file to your printer).

At the same time, your internet service provider (ISP) assigns your router a public IP address. All the devices connected to that router share this one public IP on the internet. That’s the address that websites and online services see when you visit a page or stream a video.

However, in some regions and on many mobile networks, ISPs don’t assign each customer a unique public IP address. Instead, they use Carrier-Grade Network Address Translation (CGNAT), in which many customers share a single public IP address. This helps providers cope with IPv4 shortages, but it also means multiple households or mobile users can appear to come from the same address.

Learn more: Read more details about different kinds of IP addresses (private vs. public and static vs. dynamic).

Public IP addresses mainly come in two formats:

- IPv4: It’s the older format, made up of four blocks of numbers (like 203.0.113.42). It’s been around since the early days of the internet and provides about 4.3 billion unique addresses; far fewer than we need now that almost every device goes online.

- IPv6: It was introduced to solve this shortage. IPv6 addresses are longer and look more complex (for example, 2601:19a:4500:8a0::3), but they support around 2128 unique addresses. That’s an astronomically larger pool than IPv4 and is more than enough for the foreseeable future.

Understanding how IP addresses work

When you load a website, watch a video, or send a message online, the data is broken into small chunks called packets. Before those packets are sent, your browser uses the Domain Name System (DNS) to translate the website’s name (like example.com) into the IP address of the server you’re trying to reach.

Each packet carries two key addresses: the source IP (where it came from) and the destination IP (where it’s going). The destination IP identifies the server you’re trying to reach, while the source IP tells that server where to send the reply.

As we explained earlier, your ISP usually assigns a single public IP address to your entire home connection, and that’s the IP the outside world sees. When multiple devices are online at once, your router uses a process called Network Address Translation (NAT) to keep track of which device sent which request, so the responses go back to the right place.

Importance of identifying the owner of an IP address

When you look up an IP address, you’ll usually see the name of the organization that manages that IP range: often an ISP, a cloud hosting company, or a large corporation. Public records for that IP also often include contact details for reporting abuse. Knowing who controls an IP block is useful in several situations.

- Security and abuse reports: If an IP address is being used for spam, hacking attempts, or other malicious activity, you need to know which network operator is responsible for it. IP ownership records indicate which organization owns the IP block and usually list an abuse contact so security teams can report the issue to the right party.

- Email and service trust: Mail providers and online services use the reputation of IP addresses (and the networks that own them) to decide how to handle traffic. If an IP range is associated with spam campaigns or risky hosting providers, systems may automatically flag, rate-limit, or block connections from those addresses.

- Troubleshooting network problems: When there are routing errors, unusual latency, or connectivity issues between networks, IT and network engineers look up who controls the IPs involved. That helps them contact the correct network operator and coordinate a fix on both sides.

- Legal identification requests: If law enforcement wants to link online activity to a real-world subscriber, they first identify which ISP owns the IP block, then send that ISP a valid legal request (such as a warrant or subpoena, depending on the jurisdiction). The ISP can then check its logs to see which customer was using that IP at a specific time, if that information is still retained.

Learn more: Find out how shared and dedicated IPs work.

Who owns an IP address?

When you connect to the internet, the IP address you use doesn’t actually belong to you. IP addresses are part of a global addressing system and are allocated and managed by a chain of organizations rather than “owned” in the traditional sense.

Individual vs. organization ownership

Strictly speaking, an IP address isn’t anyone’s property. Even legacy address space allocated before today’s registry policies existed is treated as a resource that organizations can use (as long as they follow regional policies), not as something they fully own in a legal sense. Every address is part of a larger block that’s registered to and managed by an organization.

For everyday internet users, that organization is usually an ISP. Your ISP assigns an IP address to your connection (often a dynamic IP that changes periodically, or a static IP that stays the same for longer). In both cases, the address remains under the ISP’s control: the provider manages the allocation and maintains records of which customer is using which IP address at any given time.

For large corporations, data centers, and hosting providers, the process can look different. They can request their own IP ranges through an ISP or an approved regional partner. These ranges are often referred to as provider-independent (PI) addresses. Unlike standard ranges issued by an ISP, a PI block can stay with an organization even if it changes upstream providers.

That still doesn’t make those IPs the organization’s property. They remain part of the global address pool and are only allocated for use under specific policies. If an organization stops using a block or no longer meets those policy requirements, the registry that issued the addresses can revoke the allocation and reassign them to someone else.

Learn more: Read our explainer on how to configure a static IP address.

What governs IP allocation?

An IP address is a leased resource assigned under strict regional and global management rules. At the top of the hierarchy is the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA), which oversees the global pool of public IP addresses. IANA allocates large address blocks to five Regional Internet Registries (RIRs), each responsible for a specific part of the world:

| RIR name | Region served |

| American Registry for Internet Numbers (ARIN) | United States, Canada, and parts of the Caribbean |

| Réseaux IP Européens Network Coordination Centre (RIPE NCC) | Europe, the Middle East, and parts of Central Asia |

| Asia-Pacific Network Information Center (APNIC) | Asia and the Pacific region |

| Latin American and Caribbean Internet Addresses Registry (LACNIC) | Latin America and the Caribbean (except areas handled by ARIN) |

| African Network Information Center (AFRINIC) | Africa |

Each RIR distributes smaller address blocks to ISPs, data centers, cloud platforms, and large organizations. These entities then assign individual IPs to their customers and users.

Every level of this system keeps detailed allocation records. ISPs, for instance, maintain logs showing which subscriber used a specific IP address at a particular time, information that can be referenced for network troubleshooting, billing, or lawful requests.

How to find out who owns an IP address

Looking up an IP address can show which organization manages it and where it’s registered. This information helps identify the network owner, not the individual user behind the connection.

Using WHOIS and Registration Data Access Protocol (RDAP) lookup tools

Most people use WHOIS to find out who manages an IP address. WHOIS is a public directory service that lets you see which organization is responsible for an IP block and how to contact them.

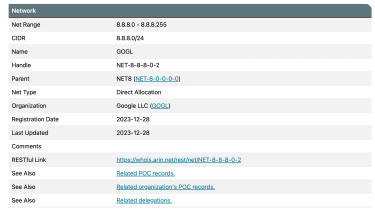

Each RIR, such as ARIN or RIPE NCC, runs its own WHOIS database. When you paste an IP address into a WHOIS lookup tool, it shows details like the organization name and the IP range.

RDAP is a newer technology that provides the same kind of registration data as WHOIS, but in a modern, structured format that is easier for software to read. You usually do not use RDAP directly; instead, IP lookup websites and security tools call RDAP behind the scenes to obtain consistent data from the appropriate regional registry, then present it to you in a human-friendly way.

How to look up IPs via RIR tools

The process is similar across registries like ARIN, RIPE NCC, and APNIC:

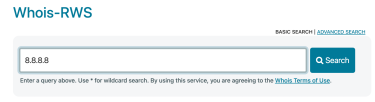

- Open your browser and go to a WHOIS site, for example, ARIN. If you are not sure of the URL, search for the registry name to find the official page.

- Paste the IP address and click Search.

- The search will return all the results relevant to the IP address you entered. You can check the fields you’re interested in, like the company name that manages the IP block, the range of IPs it manages (Net Range), the registry date, etc.

If you don’t know beforehand which RIR an IP address belongs to, ARIN is a good place to start, as it tells you which registry to look it up at.

Best free IP lookup services

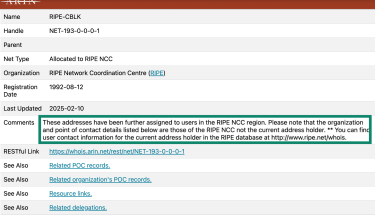

Unlike WHOIS and RDAP, which focus on who an IP block is registered to, these services combine registry data with geolocation and network intelligence to help you understand how an IP is being used in practice.

- IPinfo: IPinfo analyzes registry data and live network insights to identify an IP’s ISP, network type (residential, business, mobile, or cloud), and whether it’s linked to a VPN or proxy. The free API tier can even spot unusual traffic patterns.

- Ipapi: This tool is built for developers who want quick geolocation and network context about an IP. Besides identifying the city and country, it shows you the timezone, language, and Autonomous System Number (ASN) details that WHOIS doesn’t. An ASN is a unique identifier for the network or organization that controls a group of IP addresses, helping you determine which provider or network an IP address belongs to.

- DB-IP: This tool comes with a free API and a downloadable database. You can look up IPs via the API or run the database locally for faster, more private, in-house lookups.

- BigDataCloud: This service focuses on next-generation IP geolocation. Its free tools can return country, region, city, detailed locality, and coordinates, plus network and ASN information.

Limitations of IP lookup accuracy

IP lookup tools can usually identify the country with high reliability, but accuracy drops the closer you get to the city or neighborhood level. City-level data often comes with a margin of error that can range from a few kilometers to entire regions, especially for mobile networks.

Another limitation is that many users share the same public IP address, especially on mobile devices or in large residential networks. CGNAT (used by many ISPs) means dozens or even hundreds of people may appear under the same IP address at once. So even if the location is approximately correct, it doesn’t identify which person was behind that activity.

If someone used a VPN, proxy, or a Tor exit node, it’s more difficult to locate them. Their traffic appears to be coming from a completely different location, and the lookup will show the VPN server's country, not the user’s actual location.

Can you be traced through an IP address?

In theory, your IP address can be used to trace activity back to you, but it’s more nuanced than that. Public IP records can show which ISP or organization manages an address and its approximate registered location, not the individual user behind a connection.

As mentioned earlier, many mobile operators and some fixed broadband providers also use CGNAT, in which multiple customers share the same public IP address. In these instances, IP-based location data is usually coarse-grained (city- or region-level), which is why a single address doesn’t cleanly map to a single household.

However, your ISP can usually determine which subscriber account was using a particular IP address at a given time by checking its internal logs (including ports and timestamps). It can disclose those details to law enforcement upon receipt of a valid legal request, such as a warrant or subpoena, depending on the jurisdiction.

Hackers can also use your IP to launch distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks that flood your connection and knock you offline, or to link your activity to other identifiers in data breaches that might later appear in underground data dumps.

Learn more: Check out more details on how to trace an IP address and what someone can do with your IP.

What a reverse IP lookup can reveal

When people look up an IP address, they’re often doing one of two things:

- Checking who provides a home or office connection (ISP and rough location).

- Checking which websites or services are hosted on a server's IP address.

The second case is where reverse IP lookups come into play.

Every website has an IP associated with the server that runs it. With reverse IP lookup, you can find domains that are tied to the same server IP. It does this by checking DNS records and public hosting databases. However, since there’s no master list of this data, reverse IP lookup relies on:

- Reverse DNS or pointer records (PTR): These are DNS records that connect an IP back to a hostname. Not every server has them set correctly, but when they are, this can hint at the domain name associated with that IP.

- Old DNS snapshots and logs: Some companies keep long-running archives of past DNS records. With this data, you can spot domains that were once hosted on the IP but aren’t anymore and find previous site owners.

- Large-scale web crawls: Web indexing projects and security scanners collect huge lists of domains and their associated IPs. By aggregating crawl data, they can show which domains currently resolve to an IP and detect mass-hosting patterns.

Reverse IP lookup itself uses publicly available infrastructure data and is commonly used for tasks like security monitoring and infrastructure management. However, attempting to use this information for unauthorized access may violate privacy laws.

Legal and ethical concerns around tracking IPs

An IP address is technical network data, but it can count as personal data if it can be linked to an identifiable person. Under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), “online identifiers” such as IP addresses are explicitly listed as examples of data that can be used to identify natural persons.

The California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA) directly lists an IP address as an example of personal information.

Because of this, tracking IP addresses over time can raise privacy concerns. Websites and services can use IP data to infer where someone is connecting from, which services they use, when they are online, and (if combined with account data or cookies) who they are.

Organisations that collect or look up IPs need a clear legal basis, must explain this processing in their privacy notices, and should minimise the length of time they retain IP data and the extent to which they share it.

Does a VPN or proxy hide IP ownership?

When you connect to the internet directly, every site you visit can see your real IP address and, by extension, your ISP and country. A VPN or proxy inserts an intermediary between you and the site. If someone were to look up the VPN or proxy-provided IP, they’d see a record unrelated to your ISP and country. That said, VPNs and proxies work a little differently.

- Proxies: A proxy relays your traffic through another server, but most proxies offer little to no security. Many don't encrypt your data at all, and some, especially transparent or poorly configured HTTP proxies, can even expose your real IP address through headers like "X-Forwarded-For."

- VPNs: A VPN encrypts all traffic passing through your device, protecting your data from your ISP, network operators, and potential attackers. Premium VPNs usually offer split tunneling, which lets you only pass specific apps and websites through the VPN tunnel. Some reputable VPNs, like ExpressVPN, also use encrypted DNS resolvers, so your DNS queries don’t leak to your ISP or a third-party DNS provider.

It’s important to keep in mind that not all proxies or VPNs provide strong privacy protections. Many proxies offer none at all, and some VPNs, especially free ones, may keep connection logs or operate out of a country that compels them to do so. In those cases, the provider could technically match timestamps and session details to a specific user.

Reputable, no-logs VPNs are different. A trusted VPN service is designed not to retain activity or connection logs that could identify users. It operates under policies and infrastructure built to prevent such data from existing in the first place. This makes a high-quality, no-logs VPN significantly more private and secure than typical proxy services or lesser VPNs.

Why VPNs are the most effective way to protect your IP

A VPN does more than just swap out your IP address. It wraps your traffic in an encrypted tunnel, so your ISP can see that you’re connected to a VPN server but not which websites you visit or anything you do on those websites. They also typically route DNS queries through secure, encrypted resolvers. This prevents DNS leaks, especially on networks where private DNS servers are blocked or inaccessible.

Good VPN apps address common leak points. A kill switch can block all traffic if the VPN connection drops, so your real IP doesn’t suddenly appear. They can handle IPv6 safely (either by tunneling it or disabling it), so sites can’t see your global IPv6 address while your IPv4 is hidden.

In many cases, you share the same VPN exit IP with other users, making it harder to associate specific activity with a single person. Combined with encrypted traffic and protections against common leaks (such as WebRTC), a device-wide VPN is one of the strongest practical ways to keep your real IP and network identity private from the sites and services you use.

For users who need a consistent IP address, for example, to reduce login prompts or access services that require a stable IP, ExpressVPN also offers a dedicated IP. While a dedicated IP is generally considered more easily traceable than a shared IP, ExpressVPN has engineered its dedicated IP system so that the address remains anonymous and cannot be tied to individual account activity.

IP leasing, resale, and private ownership

What is IP leasing, and why businesses use it

IP leasing is the rental of the right to use an IP block for a set period, with the original holder usually remaining the registered resource holder in the RIR database. The lessee, however, gets the right to route that space and announce it from their own ASN, subject to RIR policy and routing configuration.

Businesses lease IPs because IPv4 addresses are scarce and expensive. Leasing is often faster than obtaining addresses from a registry, avoids large up-front purchase costs, and can be easier to align with short- or medium-term projects.

Another common reason is reputational control. Email providers, Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) operators, and fraud-prevention platforms often prefer “clean” ranges with no history of spam or abuse. Leasing from providers that vet and monitor their space helps them avoid ranges already listed on blocklists such as the Spamhaus Blocklist (SBL) or the Exploits Blocklist (XBL).

Can you buy or sell an IP address?

As already mentioned, you can’t technically “own” an IP address as property. What you can do is transfer the right to use an IP block under the registry’s transfer policy for your region. In practice, organizations “buy” and “sell” these usage rights, but the transfers have to be recorded in the relevant RIR database.

| RIR name | Minimum transfer size | Inter-RIR transfers |

| ARIN | /24 (at least 256 IPv4 addresses) | Yes (RIPE, APNIC, and LACNIC) |

| RIPE NCC | No formal minimum, but /32 for IPv6 and /48 for IPv6 PI | Yes (ARIN, APNIC, and LACNIC) |

| APNIC | /24 | Yes (ARIN, RIPE, and LACNIC) |

| LACNIC | /24 | Yes (ARIN, RIPE, and APNIC) |

| AFRINIC | /24 | No |

Legal and compliance considerations

The registry record determines who holds responsibility for an IP block, not the commercial agreement alone. When one organization leases space to another, both sides must update the registry to show who operates the block. If the registry entry doesn’t match the real operator, networks may distrust and block traffic from it.

The operator must also prove that the IP block belongs to them. To do that, they need to set up two routing authorization steps that other networks can verify:

- Create a Resource Public Key Infrastructure - Route Origin Authorization (RPKI ROA): This is a signed, verifiable record that announces which networks are allowed to use and announce an IP block. When other networks see this, they know to trust your traffic and ignore anyone else using the same IPs.

- Publish matching Internet Routing Registry (IRR) route/route6 objects: This is like a public phonebook entry for your IP block. It tells the rest of the internet that if you want to reach these IPs, send the traffic through this network. Without it, your traffic can be blocked or treated as suspicious.

You should also monitor the reputation of your IPs. Many leased or recently transferred blocks appear on blocklists such as Spamhaus SBL or XBL if past tenants used them for spam. Cleaning those records prevents delivery issues and reputation damage.

To keep geolocation accurate, publish a Geofeed file, as defined in Request for Comments (RFC) 8805 and RFC 9632. It maps your prefixes to the countries or regions they actually serve, reducing issues with region-locked content or fraud-detection tools that misplace traffic.

FAQ: Common questions about who owns an IP address

Can I find out who an IP address belongs to for free?

Yes, WHOIS and Registration Data Access Protocol (RDAP) let you look up basic details about an IP address. These include the name of the organization that currently holds it, the range of IPs they have, and contact details for reporting abuse. You can’t identify the person who’s using a specific IP address with an IP lookup, though.

Is it legal to look up an IP address?

Yes, a basic IP lookup is legal because the data is publicly available. However, privacy laws in different countries limit how you can use this information. IP addresses can be considered personal data if they can be linked to a specific person, so attempting to identify an individual using their IP address without a legal basis can be unlawful.

Can I buy my own IP address?

You can’t buy an IP address like a commodity, but you can acquire the right to use one through a registry-approved transfer. At an individual level, VPNs and hosting services provide paid dedicated IPs that give you the same IP every time. However, these are just assigned to you as a paid add-on service and don’t belong to you.

How much does it cost to own an IP address?

You can’t own IP addresses, but you can acquire the right to use them. Fees vary by registry. For instance, the Regional Internet Registry for Europe, the Middle East, and parts of Central Asia (RIPE NCC) charges a flat annual maintenance fee on a pro rata basis, while the Asia Pacific Network Information Centre (APNIC) bills you based on the size of your IP block.

Can I create my own IP address?

You can’t create your own public IP address. These come from your internet service provider (ISP) or a regional registry, so the global internet knows where to send traffic. You can, however, create your own private IPs on your home or office network. These come from special “private use” ranges, defined in a standard called Request for Comments (RFC) 1918, that are set aside specifically for internal networks.

How do I protect my IP from being traced?

The easiest way to prevent your IP from being traced is to use a reputable VPN, which replaces the IP websites see and encrypts your traffic so others on your network can’t see what you’re doing. Your internet service provider (ISP) will still know you’re using a VPN, but it can’t see which sites you visit.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN