It’s official: Yesterday we wrote about a new data retention law in Australia that compels ISPs to save user “metadata” for two years and supply it without a warrant on demand from federal agencies. The result? More Australians are interested in virtual private networks (VPNs) as a way to protect their actions online.

From All Sides

The assault on digital privacy isn’t just happening at the hands of the country’s new legislation. According to Torrent Freak, the Dallas Buyers Club (DBC) that produced the motion picture of the same name applied for permission to obtain metadata on 4,726 consumers who illegally downloaded the movie from file-sharing sites. The answer from Australian courts? Yes, with certain restrictions. While ISPs will be compelled to provide subscriber information, warning letters sent to downloaders must be vetted by the court.

While the fortunes of just under 5,000 users seem trivial in the scope of millions, the court decision sets a dangerous precedent when combined with other efforts in the works. In addition to the country’s recent data retention legislation — which includes no specified destruction period or notification to users if their data is accessed — the government is also considering a three-strikes system for users and site-blocking legislation to hamper illegal downloads. While high-minded, both of these solutions open the door for significant violations of users’ digital privacy.

Here’s Your Answer

With data under assault on all sides, Australian users are taking steps to protect themselves. According to a recent poll by Essential Research, 74 percent of users now clear cookies in their browser history, while 50 percent have disabled cookies and 51 percent have stopped using websites that may be collecting personal information. But that’s just the beginning — now, 36 percent say they’re opting for untraceable usernames, 31 are using non-identifiable email addresses, and 16 percent are now using a VPN or Tor software to obfuscate their activities online.

Taken at face value, 16 percent doesn’t seem like a lot, but consider that the number of Google searches for “VPN” has quadrupled in Australia over the last few weeks. Once regarded as technology for extremely tech-savvy users or high-level politicos who required anonymity, the idea of complete online privacy is quickly gaining appeal among ordinary citizens. Why? Because it’s no longer about having “something to hide” but rather the firm conviction that governments and law enforcement agencies need to ask before taking and must provide users notification if metadata is being used as part of an investigation. In other words, the onus is on governments to prove the need for access, not on users to justify their demand for privacy.

Warning Shots

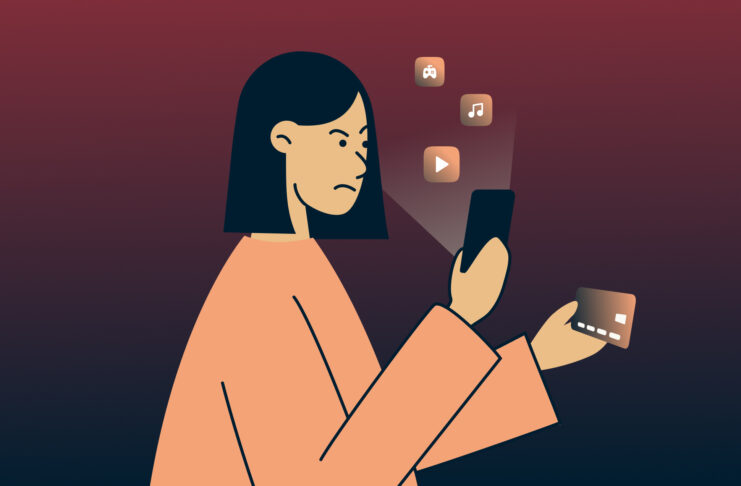

The fight for digital rights has ignited a firestorm in Australia but is fanning flames across the globe. For example, Netflix just updated its terms and conditions, Article 6c, to state that:

“You may view a movie or TV show through the Netflix service primarily within the country in which you have established your account and only in geographic locations where we offer our service and have licensed such movie or TV show. The content that may be available to watch will vary by geographic location. Netflix will use technologies to verify your geographic location.”

While the new terms don’t mention VPNs and Tors, that’s the idea: Watch content how and where you’re not supposed to, and your account could be suspended. While the company says it has no plans to crack down on VPN users, studios are likely pushing for this kind of warning shot to let users know they have to play by the rules.

But here’s the thing: In Australia and the rest of the world, rules are changing. As more and more users opt for privacy over the assumption of government and corporate good will, some backlash is inevitable. Once enough citizens have made the switch, however, and take back the privacy that’s rightly theirs, expect government tunes to change.

Featured image: Edelweiss / Dollar Photo Club

Comments

All I want is to access the this network